Justina Crabtree | @jlacrabtree CNBC

Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn resigned last week following anti-government protests. A state of emergency has since been imposed on the country.

Ethiopia is one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, having achieved double-digit gross domestic product growth in recent years.

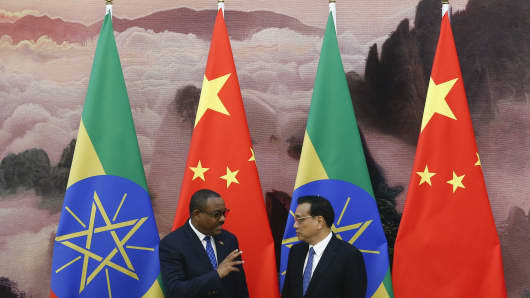

China provides much of Ethiopia’s foreign direct investment, and the east African country is a linchpin of China’s Belt and Road infrastructure scheme.

China provides much of Ethiopia’s foreign direct investment, and the east African country is a linchpin of China’s Belt and Road infrastructure scheme.

Ethiopia is one of the world’s fastest growing economies and a hub for Chinese investment, having rejuvenated its fortunes after a turbulent history marred by civil war and famine.

But, the East African nation’s political story is murkier. Given the surprise resignation of its prime minister and the declaration of a state of emergency last week following protests, CNBC takes a closer look at this major frontier market.

Set up for political failure

Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn resigned on February 15 following mass protests. A six-month long state of emergency was imposed by the government the next day, with the intention of quelling civil unrest.

The state of emergency prohibits, among other things, the distribution of potentially sensitive material and unauthorized demonstrations or meetings.

Hailemariam remains in office until a new prime minister is appointed.

Ethiopia is, in essence, a one party state led by the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, a coalition comprising of parties representing different regions of the country.

Tension has been bristling between the powerful Tigray People’s Liberation front, which represents just 6 percent of Ethiopians, and its counterparts representing the Amhara and Oromo ethnic groups. Meanwhile, Hailemariam’s party, the Southern Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement, is the weakest in the coalition.

Hailemariam, who took power after the death of his predecessor Meles Zenawi in 2012, has failed to unite his party. The former leader headed up a centralized government and wielded prestige from the country’s civil war to ensure loyalty.

Anti-government protests have bubbled up, most recently in 2016 when the country’s last state of emergency was imposed.

“It is unlikely (Hailemariam’s) successor will adopt a more reformist stance,” Emma Gordon, senior East Africa politics analyst at consultancy Verisk Maplecroft, told CNBC via email. “Protests and political uncertainty will therefore continue.”

Sky-rocketing economic growth

The potential for new leadership in Ethiopia is little more than a band aid.

“The factors that have driven the protests — namely the ethnic federal system, the influence of the military and intelligence services, and the interplay between the political elites and the business sector — will remain in place,” Gordon said.

Ethiopia, one of the least developed economies in the world, has achieved double-digit growth in recent years. Should its incoming prime minister placate ethnic tensions along party lines — leading to the lifting of the state of emergency within six months — this could continue.

“Assuming (a) more benign political outcome, we expect economic growth to remain healthy, albeit below the 11 percent annual expansion targeted by the government’s Growth and Transformation Plan,” Jane Morley, regional manager for the Middle East and Africa at the Economist Intelligence Unit, told CNBC via email.

The plan includes investing $20 billion in the power sector, and boosting the number of tourists visiting the country to 2.5 million annually.

Morley placed the expected gross domestic product (GDP) growth figure at 7-7.5 percent annually over the next five years, thanks to “growing consumer markets, greater integration into global and regional value chains and continued infrastructure investment.”

Belt and Road linchpin

Ethiopia is a key partner of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a massive infrastructure spending push to resurrect ancient trading routes centred on China. This is partly because of its strategic location neighboring the tiny port state Djibouti, at which China has a naval base. A maritime presence in the region enables access to European markets via the Suez Canal.

Ethiopia is also attractive because of its low cost labor, transport links and a vast consumer market — with its population of over 100 million making it Africa’s second largest.

Although foreign direct investment (FDI) to Ethiopia has been hampered by unrest in recent years, this remains on an upwards trajectory. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, Ethiopia attracted $4.2 billion in the fiscal year of 2016-17.

Morley said: “This is partly because large amounts of FDI is Chinese, going into industrial parks, and concerns about human rights and repression have proved less of a deterrent than might be the case with some Western states.”

No comments:

Post a Comment